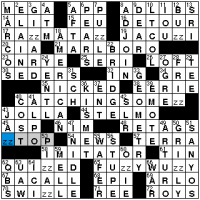

“What the hell? The answer has to be ZZ TOP! But it’s four letters and not five… I know ZZ TOP is spelled with two Z’s… all the crossings fit for T and O and P… what the hell what the hell what the hell the down answer doesn’t fit either! It looks like it should be JAZZ, but that can’t… wait… waaaaaaaait.”

“What the hell? The answer has to be ZZ TOP! But it’s four letters and not five… I know ZZ TOP is spelled with two Z’s… all the crossings fit for T and O and P… what the hell what the hell what the hell the down answer doesn’t fit either! It looks like it should be JAZZ, but that can’t… wait… waaaaaaaait.”

Solving a rebus usually means at least a few moments of boiling frustration like this. The answer doesn’t fit the letter-spaces required of it! ILLOGICAL. ILLOGICAL. Hopefully this is followed by the guessing of the rebus, and then by the brief euphoria of playing the crossword game in “god mode.” You can discover eight, ten, even fifteen words that can defy their allotted letter-count, and once you’re in on the trick, it’s as if you yourself are making four equal five!

If rebuses had been less popular, computerized means of constructing and solving crosswords might have almost finished them off, merely by making them too impractical to construct or solve. Even now, those technologies are sort of grouchy about including them. When I make a rebus, Crossword Compiler asks me to assign special “square properties” to each rebus square, as well as a “single letter” for the “main central text.” Then, when I open the clue editor, it lists the word using that “single letter.” ZZ TOP would be ZTOP. Then my solvers struggle to fill in the blank. (Normally, when I realize I’m solving a rebus online, I either write in the first letter of the missing string or hit the “fill letter” button.) In a way, Crossword Compiler doesn’t seem to accept that the correct way to fill in the aforementioned square is ZZ… it just indulges us a little. It’s like when one of my relatives tells me that having a Facebook account may lead directly to my death, and I just nod silently.

One way around this anti-rebusism is to use the various non-alphabetic characters in expressive ways: any of the 0-9 numerals for their corresponding number, ! for BANG, @ for AT, # for POUND or NUMBER, $ for DOLLAR… %, ^, &, *, -, +, _, /, :, ,, .. This is, however, a fairly limited set to work with.

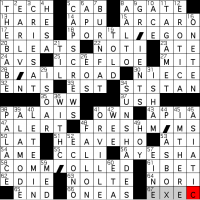

There’s no particular restriction on rebus strings that are too easy: ZZ is fairly common, and using AT led to what may be the densest rebus ever published in papers. But the more uncommon the strings, the harder it is to construct something that really sings. Matt Gaffney’s AND/OR rebus may be close to the limit: he manages to work in PORTL[AND OR]EGON, GR[AND OR]IENTS, B [AND O R]AILROAD, EARL V[AN DOR]N, FRESHM[AN DOR]MS, P[ANDOR]A’S BOX, COMM[ANDO R]OLLED and WITH C[ANDOR].

There’s no particular restriction on rebus strings that are too easy: ZZ is fairly common, and using AT led to what may be the densest rebus ever published in papers. But the more uncommon the strings, the harder it is to construct something that really sings. Matt Gaffney’s AND/OR rebus may be close to the limit: he manages to work in PORTL[AND OR]EGON, GR[AND OR]IENTS, B [AND O R]AILROAD, EARL V[AN DOR]N, FRESHM[AN DOR]MS, P[ANDOR]A’S BOX, COMM[ANDO R]OLLED and WITH C[ANDOR].

Part of what makes a rebus vibrant and fun is that its rebus string doesn’t monopolize… or monotonize… its entries. One could probably work out a rebus with the string TRANSFORMERS, but after [TRANSFORMERS] DARK OF THE MOON and BROKEN [TRANSFORMERS], all I can think of is more movie titles or dull variants like THE [TRANSFORMERS]. (TRANSFORMERS pretty much demands an anagram theme, anyway.)

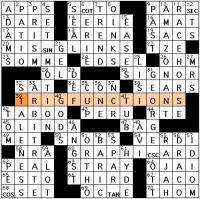

While the single fixed string, like the examples above, is the most common type of rebus, you do see the other three types on occasion. Next most common is the multiple fixed string rebus. In this Julian Lim, there are six rebus squares, each using a different string that corresponds to the common abbreviations of TRIG FUNCTIONS. Multiple fixed strings need some sort of theme like that to bind their rebus squares together, lest they get too unpredictable and hence annoying. As a bonus, the rebus squares are arranged symmetrically, with each symmetrical pair (SIN-CSC, TAN-COT, COS-SEC) matching each trigonometric operation to its opposite. Symmetrical square placement like this is more the exception than the rule: gratifying variations on a rebus theme rarely line their rebus squares up so precisely.

While the single fixed string, like the examples above, is the most common type of rebus, you do see the other three types on occasion. Next most common is the multiple fixed string rebus. In this Julian Lim, there are six rebus squares, each using a different string that corresponds to the common abbreviations of TRIG FUNCTIONS. Multiple fixed strings need some sort of theme like that to bind their rebus squares together, lest they get too unpredictable and hence annoying. As a bonus, the rebus squares are arranged symmetrically, with each symmetrical pair (SIN-CSC, TAN-COT, COS-SEC) matching each trigonometric operation to its opposite. Symmetrical square placement like this is more the exception than the rule: gratifying variations on a rebus theme rarely line their rebus squares up so precisely.

The single variable string is trickier but not unheard of. In this Peter Gordon, the variable string is [GRAY/GREY], and each Across-Down pair features one of each. It works well, because GRAY/GREY is one of the most commonly used words with two widely accepted and used variant spellings, a lot more common than THEATER/THEATRE.

The single variable string is trickier but not unheard of. In this Peter Gordon, the variable string is [GRAY/GREY], and each Across-Down pair features one of each. It works well, because GRAY/GREY is one of the most commonly used words with two widely accepted and used variant spellings, a lot more common than THEATER/THEATRE.

Variable strings really bring the conflict between computers and creativity to a head. Constructing and solving programs only understand crosswords in terms of letter-strings, but neither filling GRAY nor GREY into the rebus squares here would really be “correct.” If one solves the crossword on paper, though, the solution presents itself: crosshatch the square lightly in pen until it takes on a grayish hue, then “read” that square as GRAY or GREY depending on the context. Once you give yourself the freedom to draw, all kinds of vistas open up. “*” can be read as STAR or BURST. A picture of a cat can be read as CAT or FELINE. A picture of God could be read as GOD or as nothing at all, if you’re an atheist looking to stir up some trouble.

Multiple variable strings step right up to the limit of what may be gettable, but this Todd McClary seems to fit the bill. It mimics a standard multiple-choice test, including four theme entries that include the mixed-in string ABCD: ANABOLIC STEROID, BASEBALL CARDS, ALBRECHT DURER and BABY DOC DUVALIER. Read down, three out of these four letters behave as normal, but the fourth one is replaced by BLACK, representing the way you “BLACK in” one of the multiple-choice entries. [BLACK] IN, [BLACK] HOLE, BOOT [BLACK], [BLACK]EN. [B/BLACK], [D/BLACK], [A/BLACK], [C/BLACK]. This kind of highly structured approach is the only way to keep something as wild as a multiple variable string from descending into complete, Lovecraftian madness.

Multiple variable strings step right up to the limit of what may be gettable, but this Todd McClary seems to fit the bill. It mimics a standard multiple-choice test, including four theme entries that include the mixed-in string ABCD: ANABOLIC STEROID, BASEBALL CARDS, ALBRECHT DURER and BABY DOC DUVALIER. Read down, three out of these four letters behave as normal, but the fourth one is replaced by BLACK, representing the way you “BLACK in” one of the multiple-choice entries. [BLACK] IN, [BLACK] HOLE, BOOT [BLACK], [BLACK]EN. [B/BLACK], [D/BLACK], [A/BLACK], [C/BLACK]. This kind of highly structured approach is the only way to keep something as wild as a multiple variable string from descending into complete, Lovecraftian madness.

The rebus has indirectly inspired a couple of intriguing, but little-practiced cousins. In a squeezeboxes puzzle, every square in the grid is a fixed rebus square. Like the anything-goes, this is a form most noticeably practiced by Trip Payne, and like the anything-goes, it deserves wider adoption… but those aforementioned computer issues are more severe in its case, and likely to slow its spread. Still, Payne’s first effort is reproduced below, in all its glory.

Vowelless puzzles don’t tax software at all. These crosswords’ clues are normal, but solvers must remove all vowels before putting the answers in the grid. The vowels are just “implied,” you see. The results can be satisfying, but intimidating to look at… how many of the real answers represented by this grid can you guess? (And could the fact that this represents a beguiling challenge all its own make the vowelless a sort of double-puzzle? Discuss.)

So far, the consonantless puzzle is purely theoretical. Such a grid’s answers, post-solution, would probably be completely unguessable.

Thus endeth our look at the trickster category. The tricksters have posed as normal everyday crosswords, sneaked into our homes, and made plenty of mischief after hours. They’ve riled up some of our more conservative solvers. But it seems clear enough that the world of crosswording would be a duller, sadder place without them.

Next time out we’ll be looking at what the mutants have to offer society. It will be difficult, but I’ll try to keep the X-Men-related jokes to a minimum.

There was this amazing crossword puzzle in the 2007 MIT Mystery Hint called UN-Speakable. In addition to being a multilingual puzzle in which you had to figure out the languages,

SPOILER WARNING

It was also a phonetic crossword—each square contained a phoneme instead of a letter or letters.

END SPOILER

And then, as in virtually all Mystery Hunt puzzles, there was another step after solving the crossword where you had to extract an answer word or phrase from the puzzle for use in the round’s metapuzzle.

Intriguing indeed, and I’ll probably quietly add it to the text of this article before the week is out.

I do so enjoy the puzzle types described here, especially the varieties like Squeezeboxes and Vowellesses.

Same, thanks for including this. Just didn’t have the chance to read it as soon as it was released. These types are some of my favorites. The toughest rebuses are those where it’s not a closed set (such as SIN,COS, etc), but a more open-ended set of possibilities (colors, animals, etc).

Amy – Frank Longo’s book of Vwlsss(!) is great. I’ve had that thing for over a year and I’m still not through them all.

Agree with Adam that the UN-speakable puzzle was cool, except for the last step, which is better described as infuriating.