You’ve probably seen this kind of crossword in school. It’s also the kind we mocked All About Steve for publishing as if it were a newspaper crossword. It doesn’t even come close to the no-uncrossed-square rule, because solvers are expected to know all the answers, and only need the slightest nudge of spatial reasoning to help. Often this kind of crossword doubles as a vocabulary test, so the name vocab crossword seems as good as any. Yes, yes, I know they’re all technically “vocabulary crosswords.” You’re very smart. (Sample from a royalty-free clipart page.)

You’ve probably seen this kind of crossword in school. It’s also the kind we mocked All About Steve for publishing as if it were a newspaper crossword. It doesn’t even come close to the no-uncrossed-square rule, because solvers are expected to know all the answers, and only need the slightest nudge of spatial reasoning to help. Often this kind of crossword doubles as a vocabulary test, so the name vocab crossword seems as good as any. Yes, yes, I know they’re all technically “vocabulary crosswords.” You’re very smart. (Sample from a royalty-free clipart page.)

Vocabulary crosswords need easy words and easy clues to be fun solves. Fun for their target audience, that is, and if you’re reading this study, that audience probably doesn’t include you. Adult solvers– especially real chest-thumping crossword-obsessives– can often forget the pleasure of first discovery that vocabs offer the newbies. This isn’t a crossword form that’s “fun for all ages,” at least not very often. I guess it would be possible to create a set of clues that were easy enough for an eight-year-old and gleefully subversive for a twenty-one-year-old.

But for the most part, these crosswords are gateway drugs to crossword addiction. I’d call them kid stuff– except that some adults lag tragically behind the rest of us in cruciverbal literacy. Some vocab crosswords use specialized vocabulary for particular adult interest groups (like the example above, aimed at Web design clients). And the crosswording bug should be spread, however it can. So the next time you see one of these stretched-out, lazy-looking grids that no paper would ever publish if they knew what was good for them… take a breath. Reflect on what they do for the community. They have a purpose! Like Dick and Jane books.

But for the most part, these crosswords are gateway drugs to crossword addiction. I’d call them kid stuff– except that some adults lag tragically behind the rest of us in cruciverbal literacy. Some vocab crosswords use specialized vocabulary for particular adult interest groups (like the example above, aimed at Web design clients). And the crosswording bug should be spread, however it can. So the next time you see one of these stretched-out, lazy-looking grids that no paper would ever publish if they knew what was good for them… take a breath. Reflect on what they do for the community. They have a purpose! Like Dick and Jane books.

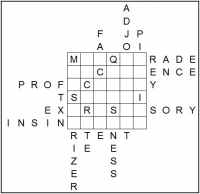

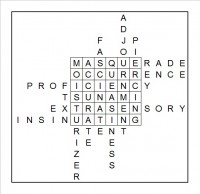

Fill-in crosswords are also called crusadexes or cruzadexes, or maybe crusadices or cruzadices, or also diagrammed crisscrosses… look, just call them fill-in crosswords. They’re structured like vocab crosswords, but instead of clues, they give you the answer words… just not where to put them. (Sometimes they’ll start you off with one word or a few letters beforehand.) The longer the words, the easier the puzzle. Fill-ins can be an easy substitute for vocab puzzles, or a hard alternative for the crossword connoisseur, and they can take the form of either vocabs or traditional American grids. (Sample from Puzzle Press.)

Fill-in crosswords are also called crusadexes or cruzadexes, or maybe crusadices or cruzadices, or also diagrammed crisscrosses… look, just call them fill-in crosswords. They’re structured like vocab crosswords, but instead of clues, they give you the answer words… just not where to put them. (Sometimes they’ll start you off with one word or a few letters beforehand.) The longer the words, the easier the puzzle. Fill-ins can be an easy substitute for vocab puzzles, or a hard alternative for the crossword connoisseur, and they can take the form of either vocabs or traditional American grids. (Sample from Puzzle Press.)

Diagramless puzzles give solvers a set of numbered clues, and an all-white grid with no black squares. You fill in the black squares as you solve, following all the hard and fast rules of American grids: no uncrossed squares, no two-letter words, all-over interlock, no repeaters. However, the percentage of black squares you’ll end up with is sometimes greater than you’d normally see in a standard American crossword. Sometimes you’re told whether the grid features left-right symmetry, up-down symmetry or the traditional radial symmetry, and/or given other starting hints.

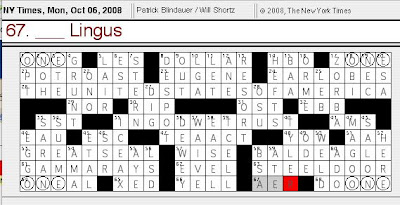

Sometimes you’re told nothing at all about the symmetry of the grid, in which case you really have to work to tease out the shape… and if that happens, the resulting shape is often highly unusual, and sometimes related to a theme found in the longest entries. Of course, such Mies-like “themed grids” can be symmetrical too. I have a fondness for themed-grid diagramlesses and the extra “aha moment” that they give to patient solvers, but it’s tough to find a good image of one. Even though the Patrick Blindauer above was not originally a diagramless, let’s just pretend that it was, because it would have been ideal for this kind of experience. Note the placement of the entries DOLLAR, THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, IN GOD WE TRUST, GREAT SEAL, BALD EAGLE, ONEg, zONE, O’NEal and do ONE.

The British have two other names for diagramlesses: “skeleton crosswords,” presumably because you build the “skeleton” of the puzzle as you solve, and “carte blanches,” from the French for “blank check,” which means free rein, presumably because the British don’t actually speak the French language. Okay, I know all this series’ British readers are already lining up to punch me in the face after the “Cryptic Crosswords” chapter, but seriously, how does “carte blanche” make a lick of sense?

The British have two other names for diagramlesses: “skeleton crosswords,” presumably because you build the “skeleton” of the puzzle as you solve, and “carte blanches,” from the French for “blank check,” which means free rein, presumably because the British don’t actually speak the French language. Okay, I know all this series’ British readers are already lining up to punch me in the face after the “Cryptic Crosswords” chapter, but seriously, how does “carte blanche” make a lick of sense?

Oh, what’s that, Joon Pahk? “Carte blanche” can also translate to “white chart?” I… I guess that’s something. But “carte blanche” still implies to me that you can just put whatever you feel like for an answer. In case you haven’t figured it out, the boldfaced names for each type are the ones with this series’ official stamp of approval.

Diagramlesses can cross over with most other kinds of crossword puzzles, like the additive example by Paula Gamache shown here.

The Daily Mail’s Blankout puzzle is like a diagramless, but clues are labeled with the rows and columns of the conventionally symmetrical grid. Compared to a conventional diagramless, not too tough to figure out, yet still eccentric enough to make you feel you’re accomplishing something special.

Crazy though it may sound, there’s also a diagramless fill-in, which works sort of like a jigsaw puzzle. Theoretically there’s only one configuration that’ll fit the given grid size, and it’s up to the solver to find it, given all the words for the puzzle but not where any of them go. Is it possible to build even on this challenge by swapping out those words for clues? The challenge is appealing, but I’m afraid that without very narrow cluing, such puzzles would yield more than one equally-correct answer. But… it is still tantalizingly possible. If the clues are narrow enough.

Split Decisions rely on a sort of double-pattern matching, and might be counted as a distant cousin of the variable crossword. All they provide is an empty, vocab-style grid and pairs of filled-in patterns, each bowed outward from the grid shape as if to say, “This grid ain’t big enough for the two of us. One of us will have to go. But which one? Because either of us could work here.” From those two choices, the solver must deduce the remaining letters. _ (KI/HO) _ _ leads to SKIRT/SHORT, and so on. This example comes from creator George Bredehorn, himself.

Split Decisions rely on a sort of double-pattern matching, and might be counted as a distant cousin of the variable crossword. All they provide is an empty, vocab-style grid and pairs of filled-in patterns, each bowed outward from the grid shape as if to say, “This grid ain’t big enough for the two of us. One of us will have to go. But which one? Because either of us could work here.” From those two choices, the solver must deduce the remaining letters. _ (KI/HO) _ _ leads to SKIRT/SHORT, and so on. This example comes from creator George Bredehorn, himself.

Crossnumbers or cross-figures are pretty much what you think they are. It’s tough to make these without resorting to mathematical expressions: there just aren’t too many numbers higher than three digits which are famous on their own. I don’t know if anyone’s tried a numerical diagramless yet. Naturally, numerical fill-in and numerical vocab puzzles exist, though to be honest with you, a numerical fill-in sounds like the most boring puzzle anyone has ever conceived. Most fill-ins get to at least invoke some kind of semantic pattern. What’s a good theme for a numerical fill-in? “Primes?” “Squares?” (Sample by Paul Niquette.)

Crossnumbers or cross-figures are pretty much what you think they are. It’s tough to make these without resorting to mathematical expressions: there just aren’t too many numbers higher than three digits which are famous on their own. I don’t know if anyone’s tried a numerical diagramless yet. Naturally, numerical fill-in and numerical vocab puzzles exist, though to be honest with you, a numerical fill-in sounds like the most boring puzzle anyone has ever conceived. Most fill-ins get to at least invoke some kind of semantic pattern. What’s a good theme for a numerical fill-in? “Primes?” “Squares?” (Sample by Paul Niquette.)

|  |

Gryptics are clueless crosswords whose answers are long words intersecting through an open grid. No more than a relative few letters are filled in at the midsection by constructors, but all the letters outside the midsection are provided. Invented by Les Foeldessy, this form is charming and original, and like the anything-goes, it deserves more practitioners than it currently has. (Images by Foeldessy.)

Word squares contain no black squares at all, and their across answers are the same as their down answers. Variants can be shaped like right triangles, diamonds or circles, just as long as they stick to that “across is down” rule. This form antedates the crossword as we know it today, and there’s a rich tradition associated with its construction that goes all the way back to Ancient Rome. The construction of ever larger word squares, up to 10x10s, has consumed the ambitions of many a constructor. The rules for word squares technically forbid the use of two-word phrases. But I’d be hella impressed if someone bent that rule to make an otherwise perfect 11×11. (Sample generated by Crux.)

Word squares contain no black squares at all, and their across answers are the same as their down answers. Variants can be shaped like right triangles, diamonds or circles, just as long as they stick to that “across is down” rule. This form antedates the crossword as we know it today, and there’s a rich tradition associated with its construction that goes all the way back to Ancient Rome. The construction of ever larger word squares, up to 10x10s, has consumed the ambitions of many a constructor. The rules for word squares technically forbid the use of two-word phrases. But I’d be hella impressed if someone bent that rule to make an otherwise perfect 11×11. (Sample generated by Crux.)

Puzzles that follow the general word-square structure, but have different across and down answers, are called double word squares.

The arrowword, or Scandinavian crossword, saves on space by converting what would be its black squares into “clue squares,” with each clue square pointing to an adjacent across or down answer. Sometimes a clue square is divided into two sections, one pointing across and one down. With such a small space to fit into, the clues had better be short. Like the word square and its variants, an arroword is nearly always themeless. Their structure generally means a few uncrossed squares are sprinkled onto the grid, but not nearly so many as in a standard cryptic crossword: two-letters are also acceptable in moderation. (Sample runs without byline at Roqa.)

The arrowword, or Scandinavian crossword, saves on space by converting what would be its black squares into “clue squares,” with each clue square pointing to an adjacent across or down answer. Sometimes a clue square is divided into two sections, one pointing across and one down. With such a small space to fit into, the clues had better be short. Like the word square and its variants, an arroword is nearly always themeless. Their structure generally means a few uncrossed squares are sprinkled onto the grid, but not nearly so many as in a standard cryptic crossword: two-letters are also acceptable in moderation. (Sample runs without byline at Roqa.)

Like Italian sonnets, the grids of foreign countries are informed by differences in language. You can bet the Germans have an easier time filling in the longer entries than the Japanese, whose grids are defined by long diagonal slashes of black squares, one square wide.

In a barred crossword, thin black bars at the edges of white squares are the only dividers between answers. Barred crosswords can cross over with almost any other genre of puzzle that normally uses black squares, including the diagramless, and so can a hybrid barred and boxed form that uses both kinds of dividers.

(Barred sample by Ross Beresford.) Cipher crosswords, also known as coded crosswords, codebreakers, code crackers, and kaidoku, cross the completed crossword grid with a cryptogram, turning each letter of the solution into an integer. Almost always, the solution will be a pangram, so the numbers will go from 1 to 26.

(Barred sample by Ross Beresford.) Cipher crosswords, also known as coded crosswords, codebreakers, code crackers, and kaidoku, cross the completed crossword grid with a cryptogram, turning each letter of the solution into an integer. Almost always, the solution will be a pangram, so the numbers will go from 1 to 26.

And finally, there’s the experimental crossword, because every good filing system needs at least one miscellaneous folder. When does an experimental stop being an experimental? When its form gains enough traction to earn a category of its own, even if that traction just comes from one dedicated constructor. We’ll return to this topic later. It deserves more attention than we can pay it here.

Typing fingers… exhausted… no more crossword types, please, no more…

No more…?

…No more?

(Ahem.)

These are the categories of crossword as I understand them today.

It is, without question, a biased selection. As a writer of fiction, I respond to the wild imagination of the anything-goes puzzle. As someone who likes to pursue new ideas energetically, I sympathize with Foeldessy as he tries to popularize the gryptic.

I’ve made a good-faith effort to include forms that excite me less, but because I spend less time with arrowwords and crossnumbers than other types, it’s possible that I’ve missed certain nuances that could better define, or even subdivide, their categories. Though I’ve researched as much as I can, some types surely escape my knowledge. And I just forgot about a couple of metamorphic types in the initial draft of Chapter 24. Thanks to Todd G and pannonica for catching those.

For all that, I hope that this proves to be a useful resource for constructors, and for those who use crossword construction to jog other parts of their brain, and for would-be expert solvers. Any artist who wants to create something new– and anyone who wants to appreciate new work– should have a clear context of what has come before, and where we are now.

Next week, a clear context of what has come before, and where we are now.

(Yeah, I know, I know. “No repeaters.”)

carte can also mean “chart” (among many other things) in french, so a legitimate (cryptic) interpretation of carte blanche is “white chart”—a perfectly apt name for a diagramless crossword.

Would “Split Decisions” be covered here? Don’t mean to be an Et al. pusher, but alas.

Fixed to accommodate both notes, thanks!

Also, took one more pass at the Cryptic Crosswords chapter. Changed little in the end, but added some sample grids that should make it an easier, breezier read.